In this session, we will will:

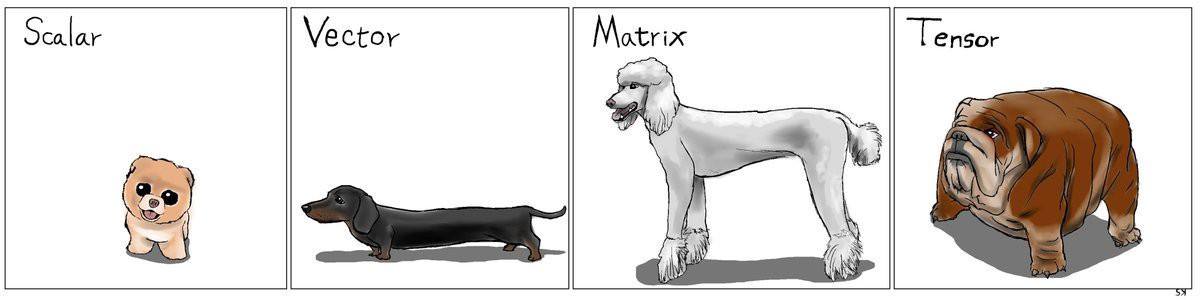

- Introduce tensors and tensor operations

- Be introduced to the basic building blocks of neural networks

- Get an insights how neural networks learn

Updated February 02, 2023

In this session, we will will:

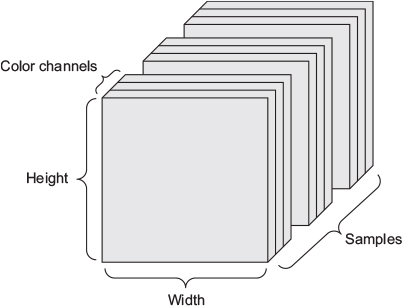

(128, 256, 256, 3)

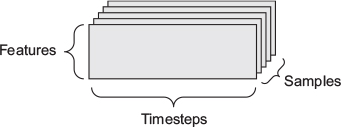

(height, width, color_depth), their sequence in a 4D tensor (frames, height, width, color_depth), and thus a batch of different videos in a 5D tensor of shape (samples, frames, height, width, color_depth).

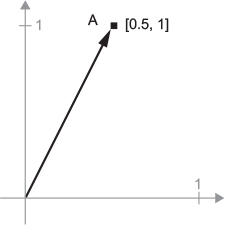

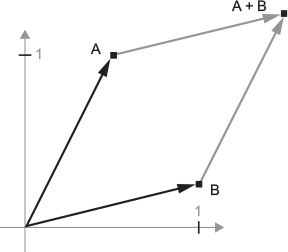

A = [0.5, 1.0]. It’s a point in a 2D space, but can also be under stood as a vector leading from the origin to this point.

B = [1, 0.25], which we will add to the previous one. This is done geometrically by chaining together the vector arrows, with the resulting location being the vector representing the sum of the previous two vectors

theta can be achieved via a dot product with a 2x2 matrix R = [u, v], where u and v are both vectors of the plane: u = [cos(theta), sin(theta)] and v = [-sin(theta), cos(theta)].

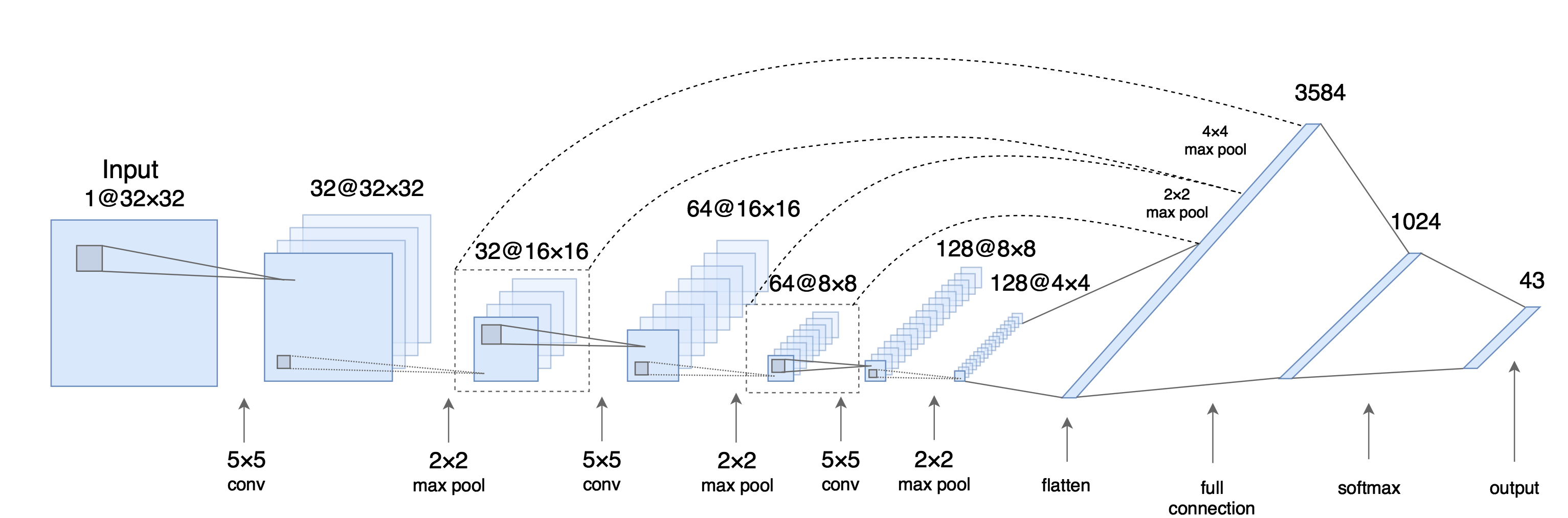

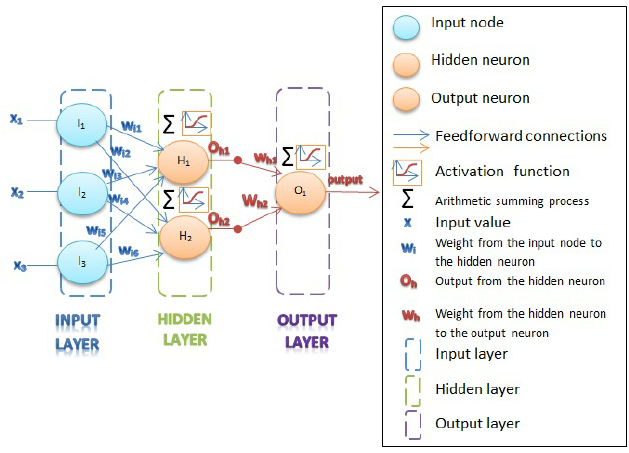

(samples, features), is often processed by densely connected layers, also called fully connected or dense layers (the layer_dense function in Keras).layer_lstm. Image data, stored in 4D tensors, is usually processed by 2D convolution layers (layer_conv_2d). All that will be introduced in later sessions.

Keras. Pytorch has a more functional programming aspproach and abstraction, but still has the layeer-stacking narrative inbuilt.

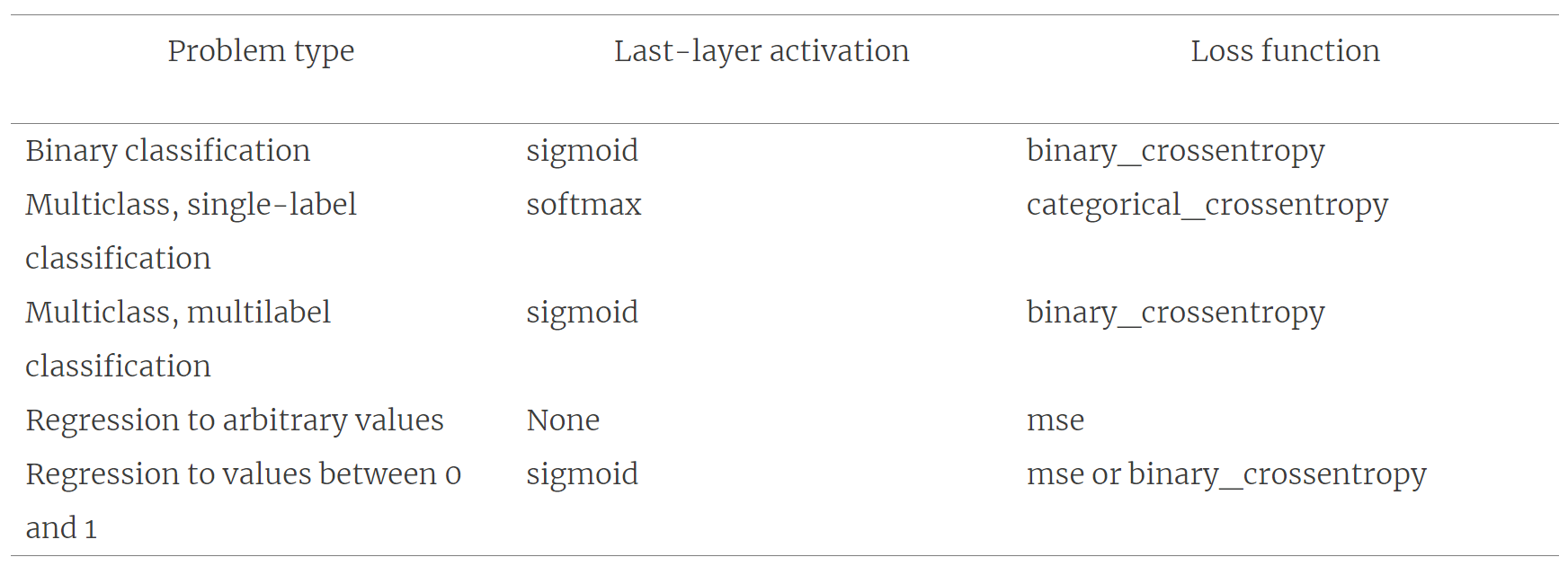

inputs from the connected other cells on lower layers which are activated, where the intensity of the input is scaled by the weight of the connection.output = activation_function(dot(W, input) + b)W and b are tensors that are attributes of the layer.dot(W, input))b), a constant which influences the tendency to activate.\(\text{softmax}(z)_i = \frac{\text{exp}(z_i)}{\sum_j \text{exp}(z_j)}\)

\(J(\theta) = -\mathbb{E}_{x, y \sim \hat{p}_\text{data}} \text{log} \ p_\text{model} (y|x)\)

*Let’s go through some basic information theory…

\(H(\text{x}) = \mathbb{E}_{\text{x} \sim P} [I(x)] = - \mathbb{E}_{\text{x} \sim P} [\text{log} P(x)]\)

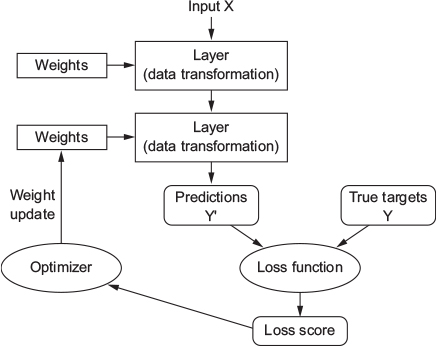

So, now we know what the deep means, and how such a deep neutwork is structured. However, we still do not know so much about the learning.

Generally, learning appears in the network by adjusting the weights between the different cells.

But how does that happen?

Initially, these weight matrices are filled with small random values (a step called random initialization).

Of course, there is no reason to expect that relu(dot(W, input) + b), when W and b are random, will yield any useful representations.

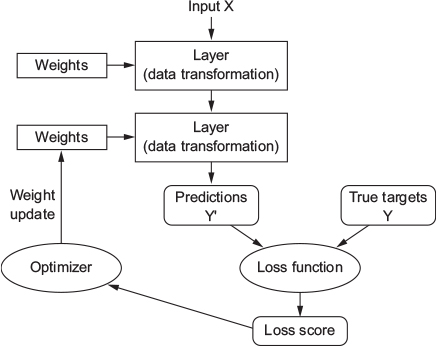

What comes next is to gradually adjust these weights, based on some feedback signal (provided by the loss function).

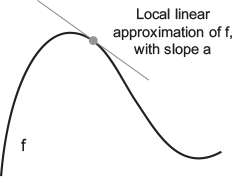

x and corresponding targets y.x (a step called the forward pass) to obtain predictions y_pred.y_pred and y.f(x) = y, mapping a real number x to a new real number y.y.x by a small factor epsilon_x: this results in a small epsilon_y change to y:f(x + epsilon_x) = y + epsilon_y

epsilon_x is small enough, around a certain point p, it’s possible to approximate f as a linear function of slope a, so that epsilon_y becomes a * epsilon_x:f(x + epsilon_x) = y + a * epsilon_x

x is close enough to p. The slope a is called the derivative of f in p.

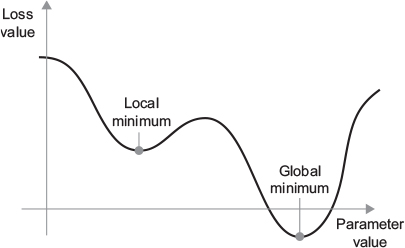

f(x), there exists a derivative function f'(x) that maps values of x to the slope of the local linear approximation of f in those points.x by a factor epsilon_x in order to minimize f(x), and you know the derivative of f, then your job is done: the derivative completely describes how f(x) evolves as you change x.f(x), you just need to move x a little in the opposite direction from the derivative.f'(x)==0, since they indicate the directional change of the curvature, and therefore local maxima or minima of f(x).f(x) is found in its second derivative, f''(x).x, a matrix W, a target y, and a loss function loss.W to compute a target candidate y_pred, and compute the loss, or mismatch, between the target candidate y_pred and the target y:

y_pred = dot(W, x)loss_value = loss(y_pred, y)x and y are frozen, then this can be interpreted as a function mapping values of W to loss values:

loss_value = f(W)

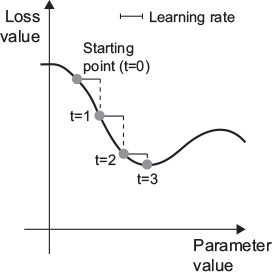

f'(x)==0indicates a local minimum, to find the global one we “only” need to identify all f'(x)==0 regions and check which has the lowest f(x).loss.If you update the weights in the opposite direction from the gradient, the loss will be a little less every time:

x and corresponding targets y.x to obtain predictions y_pred.y_pred and y.loss with regard to the network’s parameters (a backward pass).W = W - (step * gradient) - thus reducing the loss on the batch a bit.

step, which we call the learning rate.

loss function within a layer.f(W1, W2, W3) = a(W1, b(W2, c(W3)))

f(g(x)) = f'(g(x)) * g'(x)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w^{(L)}}\)

$ = $

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w^{(L)}} = h^{(L-1)} \cdot g'(z^{(L)}) \cdot 2(h^{(L)} - y)\)

\(\frac{\partial J}{\partial w^{(L)}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^{n} \frac{\partial J_i}{\partial w^{(L)}}\)

\(\nabla_{\theta}J(\theta) = \Big[\frac{\partial J}{\partial w^{(1)}} \frac{\partial J}{\partial b^{(1)}} \frac{\partial J}{\partial w^{(2)}} \frac{\partial J}{\partial b^{(2)}} \frac{\partial J}{\partial w^{(3)}} \frac{\partial J}{\partial b^{(3)}} \Big]^T\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L-1)}}\)

\(= \frac{\partial z^{(L)}}{\partial h^{(L-1)}} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L)}}{\partial z^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L)}}\)

\(= w^{(L)} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L)}}{\partial z^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L)}}\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w^{(L-1)}}\)

\(= \frac{\partial z^{(L-1)}}{\partial w^{(L-1)}} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L-1)}}{\partial z^{(L-1)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L-1)}}\)

\(= \frac{\partial z^{(L-1)}}{\partial w^{(L-1)}} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L-1)}}{\partial z^{(L-1)}} \cdot w^{(L)} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L)}}{\partial z^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L)}}\)

\(\theta \leftarrow \theta - \epsilon \nabla_{\theta}J(\theta)\)

where \(\epsilon\) is the , a positive scalar determining the size of the step

\(g = \frac{1}{m'} \nabla_{\theta} \sum_{i = 1}^{m'} L(x^{(i)}, y^{(i)}, \theta)\)

\(\theta \leftarrow \theta - \epsilon g\)

\(J_1 = \sum_{j = 1}^{n_L} (h_j^{(L)} - y_j)^2\)

\(z_j^{(L)} = w_{j1}^{(L)} h_{1}^{(L-1)} + w_{j2}^{(L)} h_{2}^{(L-1)} + w_{j3}^{(L)} h_{3}^{(L-1)} + b_{j}^{(L)}\), and: \(h_{j}^{(L)} = g(z_j^{(L)})\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w_{jk}^{(L)}} = \frac{\partial z^{(L)}}{\partial w_{jk}^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial h^{(L)}}{\partial z^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h^{(L)}}\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{k}^{(L-1)}} = \sum_{j = 1}^{n_L} \frac{\partial z_{j}^{(L)}}{\partial h_{k}^{(L-1)}} \cdot \frac{\partial h_{j}^{(L)}}{\partial z_{j}^{(L)}} \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{j}^{(L)}}\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w_{jk}^{(\ell)}}\)

\(= h_{k}^{(\ell-1)} \cdot g'(z_{j}^{(\ell)}) \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{j}^{(\ell)}}\)

\(= h_{k}^{(\ell-1)} \cdot g'(z_{j}^{(\ell)}) \cdot \sum_{j = 1}^{n_{\ell+1}} w_{jk}^{(\ell+1)} \cdot g'(z_{j}^{(\ell+1)}) \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{j}^{(\ell+1)}}\)

\(\frac{\partial J_1}{\partial w_{11}^{(L-1)}}\)

\(= h_{1}^{(L-2)} \cdot g'(z_{1}^{(L-1)}) \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{1}^{(L-1)}}\)

\(= h_{1}^{(L-2)} \cdot g'(z_{1}^{(L-1)}) \cdot \sum_{j = 1}^{n_{L}} w_{j1}^{(L)} \cdot g'(z_{j}^{(L)}) \cdot \frac{\partial J_1}{\partial h_{j}^{(L)}}\)