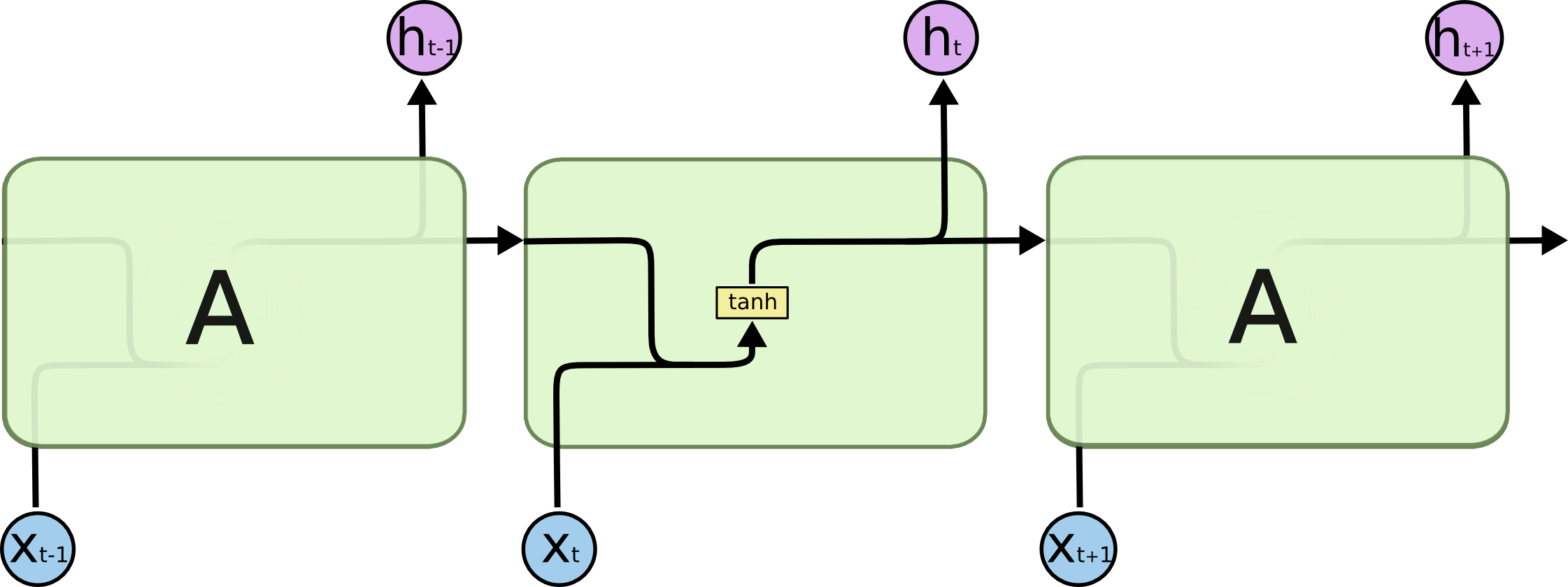

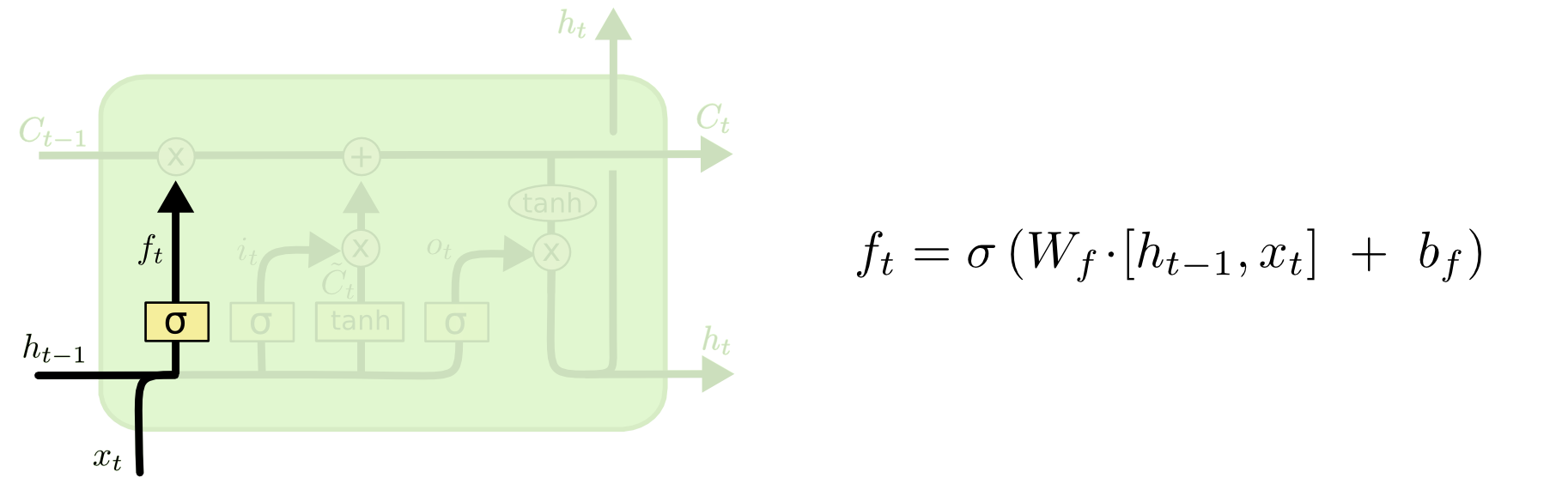

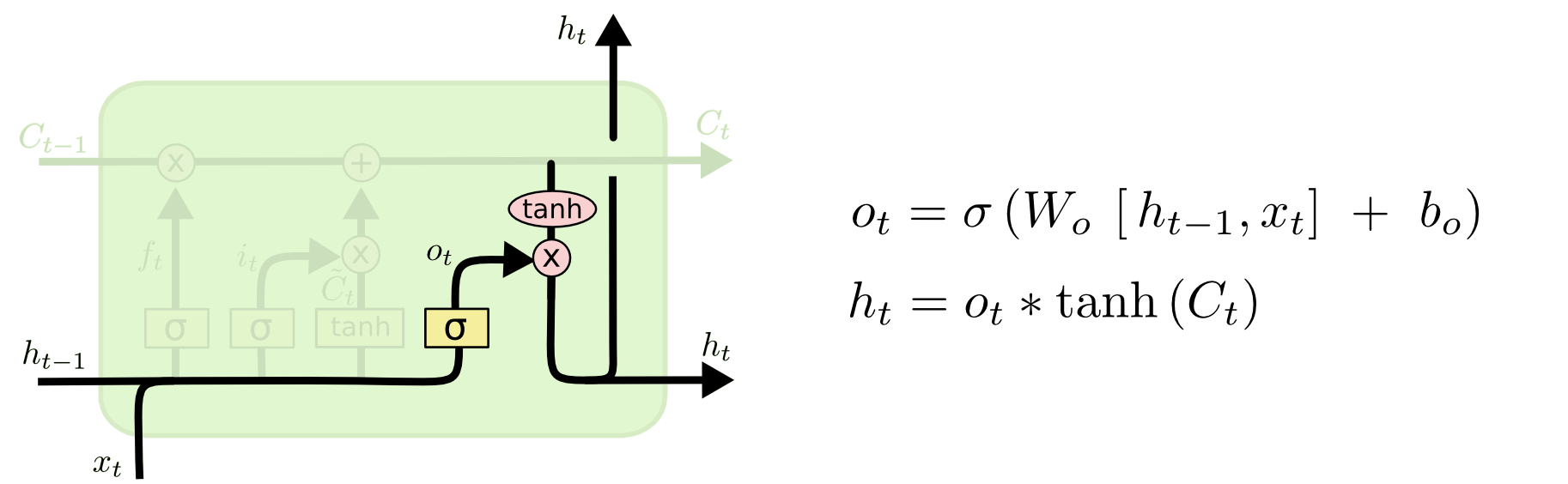

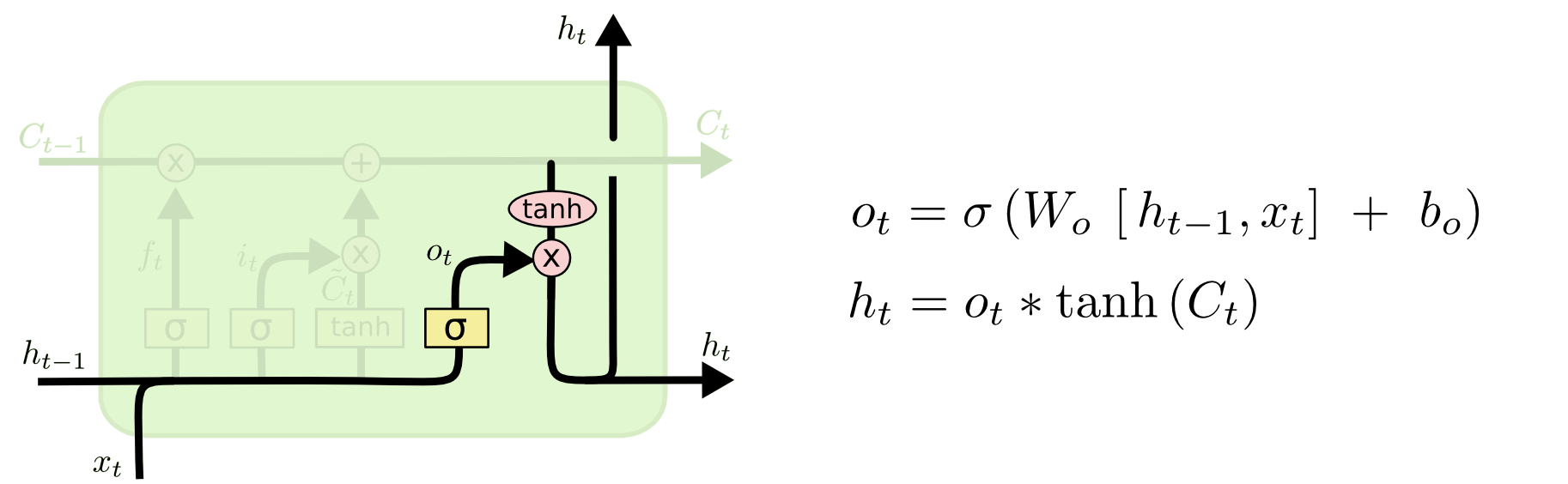

- Finally, we need to decide what we’re going to output. This output will be based on our cell state, but will be a filtered version.

- First, we run a

sigmoid layer which decides what parts of the cell state we’re going to output.

- Then, we put the cell state through

tanh (to push the values to be between [−1,1]) and multiply it by the output of the sigmoid gate, so that we only output the parts we decided to.

For the language model example, since it just saw a subject, it might want to output information relevant to a verb, in case that’s what is coming next. For example, it might output whether the subject is singular or plural, so that we know what form a verb should be conjugated into if that’s what follows next.